solved by ![]() tomato

tomato

Uh, I modified the fake onion and now it’s hoarding flags with an unreversable cipher?? Please pilfer them for me.

1 | #!/usr/local/bin/python3 import hmac from os import urandom def strxor(a: bytes, b: bytes): return bytes([x ^ y for x, y in zip(a, b)]) class Cipher: def __init__(self, key: bytes): self.key = key self.block_size = 16 self.rounds = 256 def F(self, x: bytes): return hmac.new(self.key, x, 'md5').digest()[:15] def encrypt(self, plaintext: bytes): plaintext = plaintext.ljust(((len(plaintext)-1)//self.block_size)*16+16, b'\x00') ciphertext = b'' for i in range(0, len(plaintext), self.block_size): block = plaintext[i:i+self.block_size] idx = 0 for _ in range(self.rounds): L, R = block[:idx]+block[idx+1:], block[idx:idx+1] L, R = strxor(L, self.F(R)), R block = L + R idx = R[0] % self.block_size ciphertext += block return ciphertext.hex() key = urandom(16) cipher = Cipher(key) flag = open('flag.txt', 'rb').read().strip() print("pilfer techies") while True: choice = input("1. Encrypt a message\n2. Get encrypted flag\n3. Exit\n> ").strip() if choice == '1': pt = input("Enter your message in hex: ").strip() pt = bytes.fromhex(pt) print(cipher.encrypt(pt)) elif choice == '2': print(cipher.encrypt(flag)) else: break print("Goodbye!") |

cipher

We have an oracle that allows us to encrypt any message we want, in addition to receiving the encrypted flag. Let’s take a look at the cipher, specifically its encrypt function.

18 | def encrypt(self, plaintext: bytes): plaintext = plaintext.ljust(((len(plaintext)-1)//self.block_size)*16+16, b'\x00') ciphertext = b'' for i in range(0, len(plaintext), self.block_size): block = plaintext[i:i+self.block_size] idx = 0 for _ in range(self.rounds): L, R = block[:idx]+block[idx+1:], block[idx:idx+1] L, R = strxor(L, self.F(R)), R block = L + R idx = R[0] % self.block_size ciphertext += block return ciphertext.hex() |

First, we pad the plaintext, and then split into blocks of 16 bytes. Then, each block undergoes a specific operation 256 times.

For this operation, idx is initialized as 0. Then R is assigned to the idxth byte of the block, and L is assigned to the block with the idxth byte removed (so everything except R).

Then, L is xored with F(R) and R is appended to the back of that, and this is the new block. Finally, idx is set to the value of R mod 16 for the next iteration.

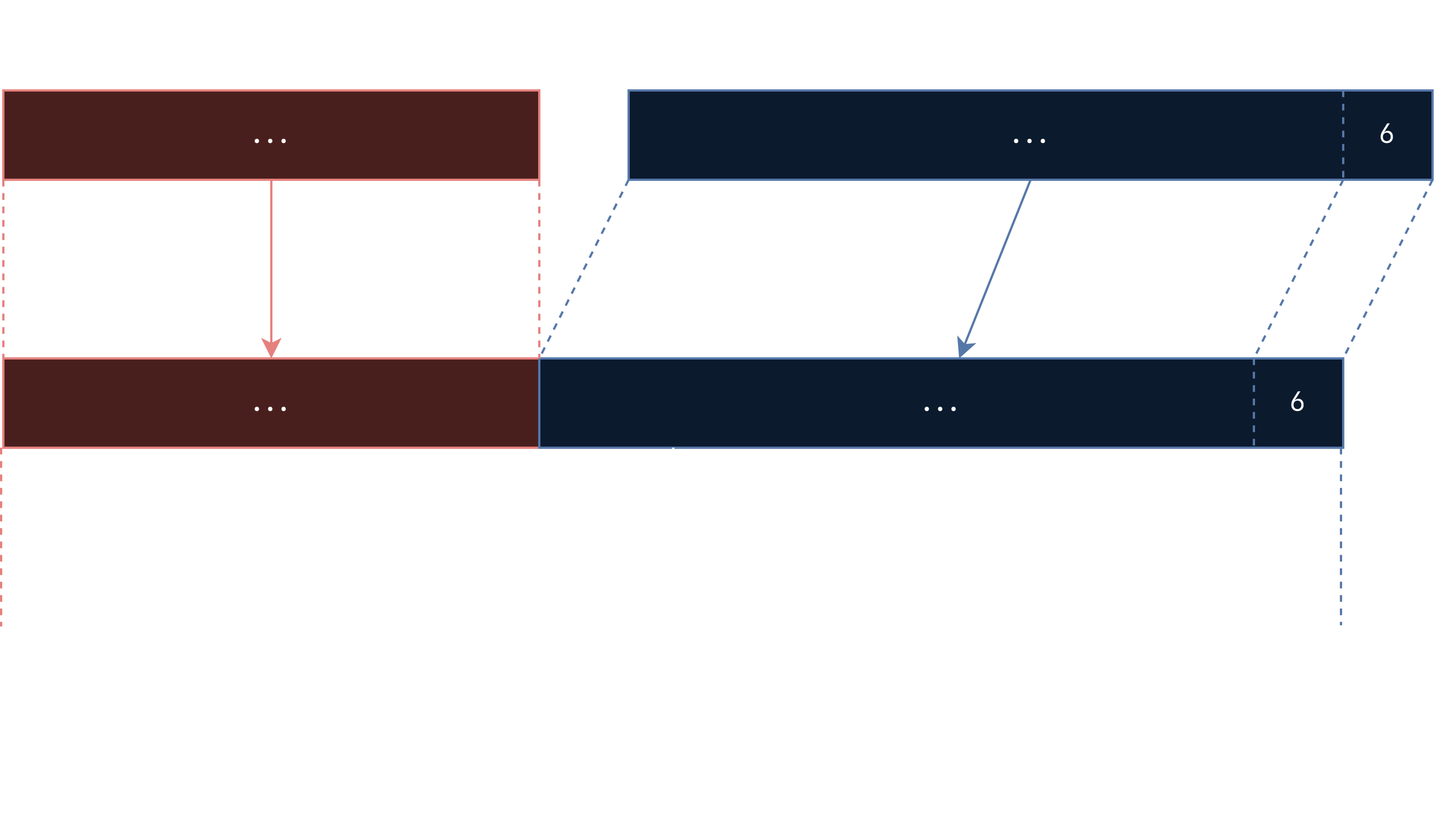

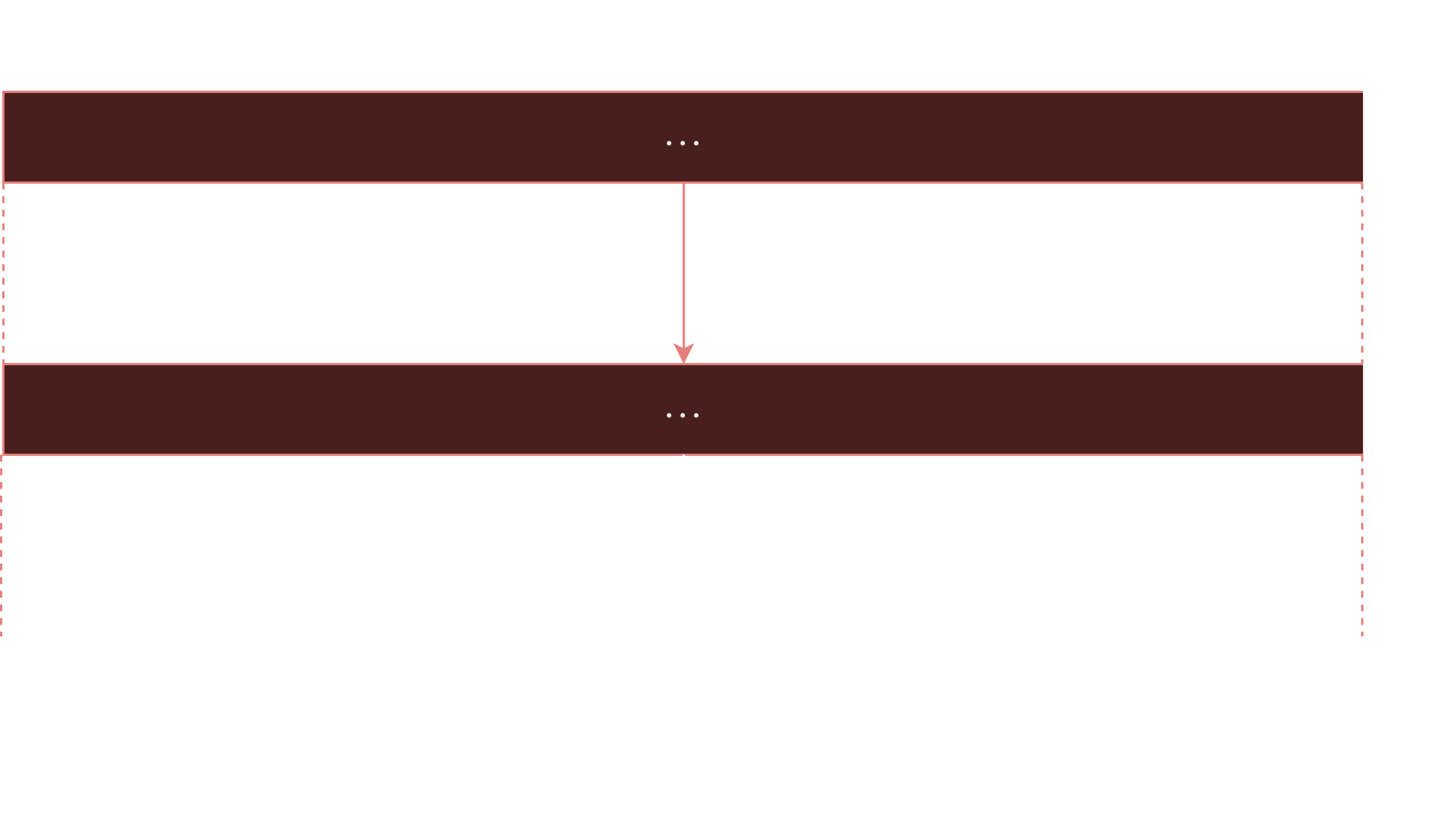

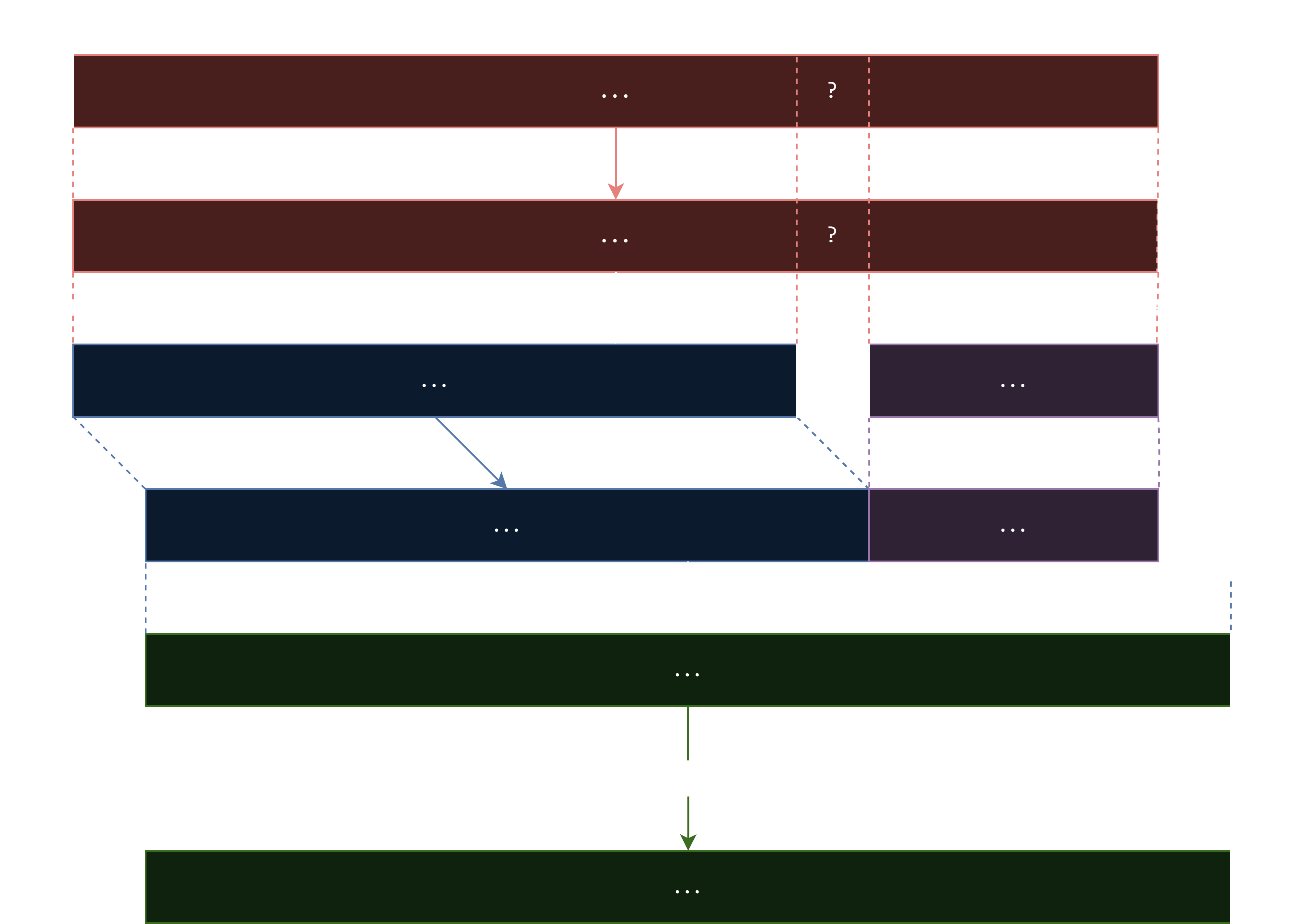

Here, F(R) is the HMAC(md5) of R with its key, which is initialized once and is always the same. Here is a visualization:

The plaintext undergoes this 256 times, so basically because we can’t compute F(R), we don’t know what gets xored as well as what index is sent for the next operation.

I first expected that there would be some singularity or cycle, like at some point the indexes would just alternate between a few numbers or just remain at one number. So, I just tested it, by printing idx at the start of every round.

key = urandom(16) cipher = Cipher(key) cipher.encrypt(b"abc") 0 13 13 11 11 11 14 11 11 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 ... |

After a while, idx just remains at 15. This is because, if R is ever a byte that is , then it would repeatedly send itself to the same index.

So, once idx reaches 15, the first 15 bytes from there are just repeatedly xored with F(R) (in this case F(31)). If there are an even number of iters remaining, it would remain unchanged, and if there were an odd number of iters remaining, it would be xored once. So, we only need to care about reversing the steps until idx reaches 15, and then possibly an additional step.

reversal (if we have F)

How can we reverse these steps though (assuming we have F)? Looking at the diagrams, the xor can be reversed by simply xor-ing the first 15 bytes with F of the last byte. Then, to reverse the movement of bytes we have to consider three cases:

- If the previous

idxwas , there is no reshuffling of blocks. - If the previous

idxwas not , then the previousidxis determined from the second last byte, and we can insert the last byte into that index. (see figure 1) - If this was the first step, then the previous

idxis 0 as initialized, so we insert the last byte at the start.

How can we tell if we need to do step 1 or step 2? Well, once idx turns 15, its forever 15. So, we can just guess that the last N steps all had idx as 15 and reverse those accordingly using the 2nd case. Since we know idx was never 15 before that, we can reverse all the remaining steps accordingly with the 1st case (apart from the first step). Implementing this:

1 | key = urandom(16) |

prints [b'amateursCTF{YUH}'], so it works. But of course, here we assumed that we have all the values of F(R) by directly calling cipher.F. Now, we have to figure out how to recover those values.

F(0)

With only the controlled inputs their outputs, we have to recover the values of F(R). Firstly, we wouldn’t want every single idx to be 15, then we would end up with pretty much the same plaintext we entered. So, we want to force the first few idxs to be numbers of our choice. For example, if we theoretically force the first idx to be 0, and the next 255 idxs to be 15, then we would be able to recover

In fact, if we were theoretically able to get the first idx to be N, and the rest to be 15, then we would get

But, as you may notice, these are the xor of two F(x). In fact, since we have a total even number of steps (256), we can only ever get the xor between an even number of F(x). So, how can we ever recover a single F(x)?

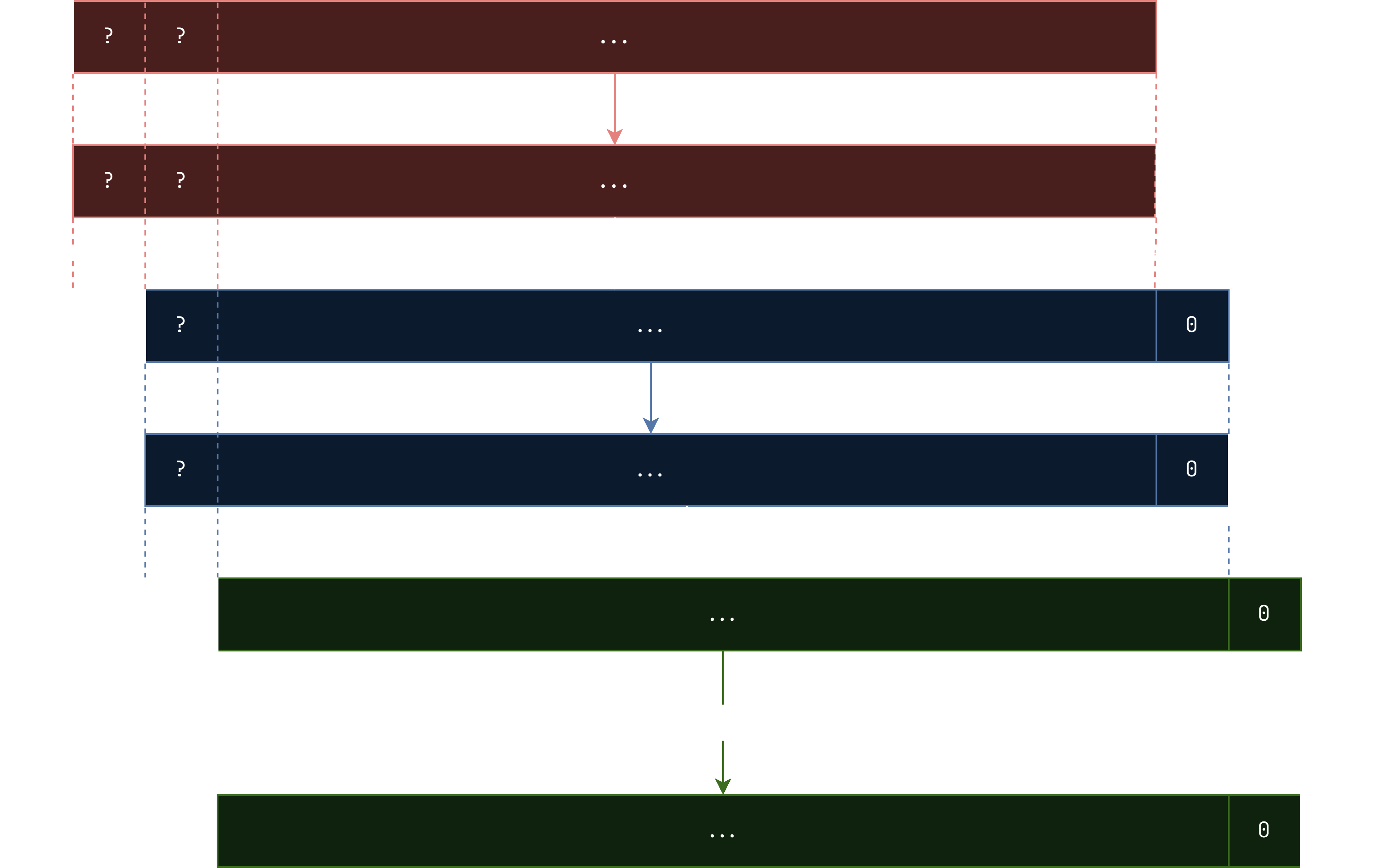

The answer is, by forcing two of the same number. Because of the movement of blocks, it is possible not to just get the F(x) to directly xor themselves, but rather, xor themselves slightly shifted. For example, if we theoretically force the first two idx to both be 0: (same colour means same values)

The plaintext is xored with F(0) twice, but the second time is off from the first time by one index. This means, that we can actually recover F(0)! You may recognize this problem from LFSRs, known as a xor-shift operation, which is reversible. To convince you, if we xor a 16-byte number x and x<<256, taking a look at the bytes, we get:

The last byte gives us , then by xoring that with we can recover , and by xoring this with we get , etc. Sort of like a cascading xor.

But how can we force the first two idxs to be 0? Looking at the diagram, the second byte has to be and the third byte has to be . Obviously we don’t know , so we would have to guess 256 bytes for each of these to even have a chance of recovering . Even so, how do we tell the bytes we tried are the correct ones?

Well, one condition we can observe from the diagram is the output has to have the last two bytes 0, 15. So, let’s see if this condition is sufficient:

1 | from Crypto.Util.number import long_to_bytes as ltb, bytes_to_long as btl |

There are still quite a few ciphertexts which also happened to end up with the same ending bytes, randomly. Is there a way to prevent this? Well, since its due to randomness, if we are able to just try each iteration more than once, it would greatly reduce the possibility of a wrong A and B producing the last two bytes of 0, 15 multiple times. And, we can control randomness, the last 13 bytes of pt don’t matter (we can xor it with ciphertext anyways), so we could just submit multiple pts with the same A and B but a different random last 13 bytes, and verify if all the ciphertexts have the same suffix of 0, 15.

But hold on. This is checks, and it takes 2 minutes even on local. Is there a way to optimize it, especially if we want to do repeat tests? Well, notice that we don’t exactly need to force out the value of 15 from the 3rd byte, any byte that is would work. Since this only involves the last 4 bits of the number, we only have to actually try 16 different B, and then now instead of checking if the last byte is 15, just check if the last byte is .

1 | from Crypto.Util.number import long_to_bytes as ltb, bytes_to_long as btl |

Just like that, we have recovered F(0)!

F(15)

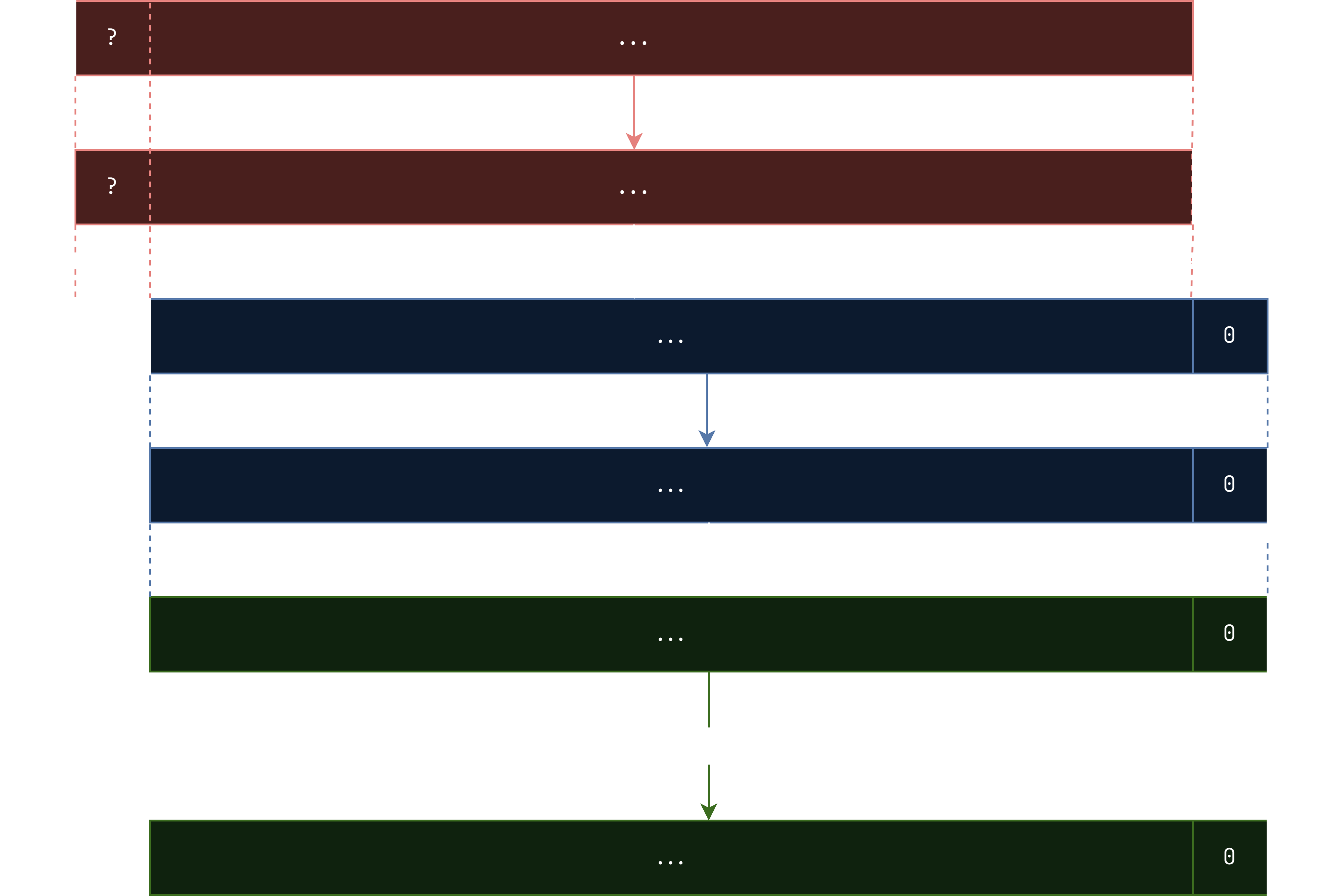

As established, we can get the xor between an even number of F(x). With F(0), we can try recovering others. We know that once idx becomes , the blocks don’t shuffle around anymore. So, if we get the first idx to be 0, and the second idx to be , the remaining 254 idxs would also be and hence cancel out, so in the end what’s left over is

(slightly shifted).

But, this time we don’t have to guess a value for the ? here, since we now know the value of F(0). We need the first byte to be after xoring with F(0), so we can just xor the first byte of F(0) with .

1 | for i in tqdm(range(15, 256, 16)): |

So, now we are able to recover F(n) for all .

F(N)

Our method to get F(15) was to set the first idx to be 0, and all 255 future idxs to be 15. Notice that the first idx being 0 isn’t actually significant, we just set it to that since we managed to get F(0) first. If we set the first idx to be N, then by forcing the rest of the idxs to be 15, we would again get

(slightly shifted).

Here, of course, we have to guess the ? that we set at the N+1th index. But again, 15 here is just an example, any number that is would work. So, we don’t have to try all 256 possible bytes, just 16 bytes. To verify if we have the correct ?, we check if the last byte is 15, and the second last byte is N xored with one of the possible F(n) (where ). Again, to minimize the possibility of a false positive, we can simply run this twice and check that the ending is correct both times. This is able to yield F(N) for all N that we have not covered so far.

1 | for n in tqdm(range(1,256)): |

solve script

Finally, we can carry out the reversal as mentioned previously. Here is the solve script I wrote on the day:

1 | from pwn import * from tqdm.notebook import tqdm from os import urandom def strxor(a: bytes, b: bytes): return bytes([x ^ y for x, y in zip(a, b)]) conn = remote("chal.amt.rs", 1415r) conn.recvuntil("> ") conn.sendline("2") CIPHERTEXT = bytes.fromhex(conn.recvline().decode().strip()) Fs={} end = bytes([0, 15]) for A in tqdm(range(256)): FOUND = False pt1 = b"" for B in range(16): for _ in range(2): pt = b"\x00" + ltb(A) + ltb(B) + os.urandom(13) pt1+=pt conn.recvuntil("> ") conn.sendline("1") conn.recvuntil(": ") conn.sendline(pt1.hex()) ct1 = conn.recvline() ct1b = bytes.fromhex(ct1.strip().decode()) for i in range(0, len(ct1b), 32): block1, block2 = ct1b[i:i+16], ct1b[i+16:i+32] if block1[-2]==0 and block1[-1]%16==15 and block2[-2]==0 and block2[-1]%16==15: print(f"found {0}") FOUND = True ct = block1 pt = pt1[i:i+16] nct = btl(strxor(ct[:14], pt[3:]+b"\x00")) cas = ltb(reduce(lambda i,j:i^^j, [nct << (k*8) for k in range(14)]) & ((1<<(14*8))-1)) #cascade xor Fs[0] = ltb(A) + cas break if FOUND: break #mod 15 for i in tqdm(range(15, 256, 16)): pt = b"\x00" + ltb(i^^Fs[0][0]) + b"\x00"*14 conn.recvuntil("> ") conn.sendline("1") conn.recvuntil(": ") conn.sendline(pt.hex()) ct = bytes.fromhex(conn.recvline().strip().decode()) Fs[i] = strxor(ct, Fs[0][1:]+b"\x00") # rest for n in tqdm(range(1,256)): if n%16!=15: ends = [(bytes([n^^(Fs[i][-1]),i]), i) for i in range(15, 256, 16)] pt = b"" for A in range(16): for _ in range(2): pt1 = list(os.urandom(16)) pt1[0] = n pt1[n%16+1] = A pt+=bytes(pt1) conn.recvuntil("> ") conn.sendline("1") conn.recvuntil(": ") conn.sendline(pt.hex()) ct1b = bytes.fromhex(conn.recvline().strip().decode()) for j in range(0, len(ct1b), 32): block1, block2 = ct1b[j:j+16], ct1b[j+16:j+32] for end, i in ends: if block1.endswith(end) and block2.endswith(end): ct = block1 pt = pt[j:j+16] print(f"found {n}") the = strxor(ct, Fs[i]) Fs[n] = strxor(pt[1:], the[:n%16]+ct[-1:]+the[n%16:]) poss = [] for N in range(256): # number of times idx was 15 c = CIPHERTEXT if N%2==1: # idx was 15 an odd number of times, xor once L, R = c[:-1], c[-1:] L = strxor(L, Fs[R[0]]) c = L + R for i in range(256-N): L, R = c[:-1], c[-1:] L = strxor(L, Fs[R[0]]) if i!=255-N: idx = L[-1]%16 # use second last byte as idx else: idx = 0 # this was the first step, idx = 0 c = L[:idx] + R + L[idx:] poss.append(c) print([i for i in poss if all(j<128 for j in i)]) |

giving the flag somewhere there: amateursCTF{i_love_cycles_4nd_cycl3s_anD_cYcl3s_AND_cyCLEs_aNd_cyc135_4319d671}